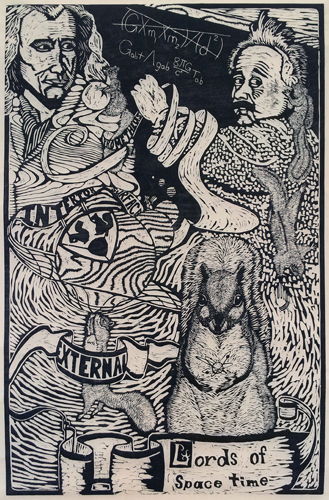

Bradley Taylor

Lords of Spacetime

In the seventeenth century squirrel had become a delicacy, which was unfortunate because squirrel populations at the time did not meet the needs of the squirrel-eating community. So in the face of their own destruction, the squirrel counsel met and decided to let mankind in on one of the biggest secrets of the universe. A spokesman was chosen to observe man, and it was decided that Isaac Newton was the most intelligent of all the physicists. The spokesman squirrel (deemed the Prometheus squirrel by modern-day scientists) won Isaac Newton's attention by throwing an apple at his head. The Prometheus squirrel then explained to a baffled Newton that squirrels had been responsible for something called gravity. The squirrel made Isaac Newton promise that he would tell the rest of mankind about the discovery in hopes of putting a stop to squirrel poaching. Newton swore that he would spread the word, but secretly he felt that the truth gave the squirrels far too much credit. He later told mankind about "his" findings—leaving out the very important detail about the squirrels—and attributed gravity to a mysterious, unseen "force" rather than to its squirrel masters. Word spread, and with that single act of treachery the squirrels went into hiding and didn't speak to another human for three hundred years.

Later, when squirrel-human relations had warmed a little, twentieth-century squirrels noticed the work of Albert Einstein and decided to trust him with the age-old secret. A squirrel spokesman told Albert in greater detail exactly how squirrels shape all space and time, the result of which creates gravity and holds the universe together. Einstein, of course, promised to tell the rest of mankind about the squirrels' great place in the universe, but instead the squirrels were burned again. Einstein reworded it, thinking people might consider him crazy for telling the world squirrels sculpt space and time. He told people gravity is not a force but just a reaction of distortions in space time. The squirrels agreed to never again talk to physicists.

And that was the last major breakthrough in mankind's understanding of gravity and space time until one day a secret page of Einstein's dairy surfaced. It told of his conversation with the squirrels. The scientific community was aghast with the shocking evidence of the truth. Despite these findings, many skeptical scientists believed that "because gravity exists throughout the entire universe and squirrels only exists on earth, then they cannot possibly be the cause of gravity." One of these scientists designed an experiment to prove that theory was true. He set out to make an isolated environment that wouldn't be effected by squirrels and therefor would have no gravity. The experiment was a success! The scientist put some cake inside the SEDC (Squirrel Effect Deprivation Chamber)—essentially a cardboard box with some dials drawn in Sharpie. It had no squirrels inside, and the scientist observed that the cake was still affected by gravity. He thought he had proved once and for all that squirrels have nothing to with gravity, but in fact what he had done was inadvertently prove the existence of interior squirrels.

Because all mass is attracted to squirrels, at the center of every mass is a squirrel or many squirrels. All celestial bodies have interior squirrels at their center and this is why the cake still had gravity. In fact, earth is the only known planet to have surface squirrels. Most scientists think it's just because our atmosphere allows it, or perhaps our planet has special gravitational needs; right now, we don't really know. There has been much dispute also about the existence of exterior squirrels which shape space time from within space itself. No one is quite sure how they do this, but many technologies are in development that might be able to prove the existence of exterior squirrels in our lifetime. One of these devices is a modified instrument that measures gravitational waves. Gravitational waves can be observed at frequency between 10−7 Hz and 1011 Hz, precisely the range in which squirrels squeak. Scientists believe that using this tool they can observe the squeaks of external squirrels.